On being a pessimist

By Greg Spearritt

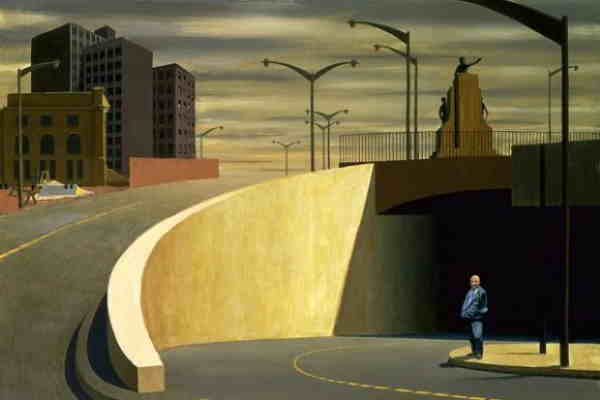

Gloomy skies. Stark, geometric, usually urban and often decaying, landscapes. Lonely, unsmiling figures.

An exhibition of the works of Australian artist Jeffrey Smart has recently concluded at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. I was among a group of SOFiA members fortunate enough to catch it in May.

Smart’s work is arresting. Though often colourful – even his ‘The Oil Drums 1992’ – there is a definite dark tone in many of his pieces. It’s a sense, for me at least, of abandonment, of loneliness, even of foreboding.

Smart captures something of how I feel about the world’s future. Yet I strongly believe this picture is incomplete.

“We must keep the flame of pessimism burning: it is a virtue for our deeply troubled times, when crude optimism is a vice.” So says Mara van der Lugt, lecturer in philosophy at St Andrews University in Scotland.

This is not the hopeless pessimism, however, that Smart’s paintings evoke in me. It’s a much more positive beast, if that doesn’t sound too much like an oxymoron.

Indeed, ‘cheerful pessimism’ concerning the fate of humanity has been my mantra for some time now. I really believe we’ll be unwilling, because of greed and stupidity, to restrict global heating and biodiversity loss until it’s too late – if it isn’t already too late. We must, however, try our best to turn things around. But there’s no point being glum when we can still find joy in many things.

Too much cheer is of course unwarranted. It could conceivably interfere with the slim chance that we could make a difference by conveying the impression that our cause is not in fact a genuine crisis.

Our pessimism, naturally, must be soundly based in the evidence, but unfortunately there is evidence aplenty. Innumerable reports from reputable scientific bodies such as the IPCC and the Convention on Biological Diversity make it crystal clear that we’re headed for trouble.

Pessimism does not have a good name, largely on the assumption that it leads to hopelessness and despair and suggests a lack of courage. In fact, the opposite can be true. I was recently made aware of a useful, if fictional, example of the need for hope and brave action even in the face of pending disaster. In Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, the Hobbits set out to defy the might of Mordor. A more hopeless task could not be imagined, yet they prevailed because they set out.

Van der Lugt persuasively argues the case:

To behold with open eyes the reality before us requires courage, and not to turn away from it, forbearance, and yet not to decide that it ends there: this is hope.

What hopeful pessimism asks… is that we strive for change without certainties, without expecting anything from our efforts other than the knowledge that we have done what we are called upon to do as moral agents in a time of change.

It’s akin, I think, to embracing the abyss. Though we don’t hold to certainty or absolute Meaning, we have everything to play for. As I see it, playing the game earnestly, but for most part cheerfully, is the task before us. I wonder how Jeffrey Smart would represent that.

Disclaimer: views represented in SOFiA articles are entirely the view of the respective authors and in no way represent an official SOFiA position. They are intended to stimulate thought, rather than present a final word on any topic.

Image from ABC Radio National.