Telling the Truth about the Colonisation of Australia: “the loss and the loneliness”

SOFiA AGM, 22 June 2024

on Yuggera and Turrbal Country

By John Carr

- We don’t know

In recent years, issues relating to Australia’s First Nations People have played a major role in SOFiA programs, website and Newsletter. In 2017, we discussed the Uluru Statement from the Heart in detail, if not with full understanding. In 2018, we studied the second edition of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu and the responses from a posse of academics. We followed the events of the Referendum campaigns and, in 2023, we analysed the results of the Referendum. From time-to-time, we have been forced to acknowledge that the objectives of the Closing the Gap movement are unlikely to be achieved in the foreseeable future.

While I was brought up in rural, working-class communities, in my old age, I live and move among other elderly, middle-class city folk and listen to their everyday comments and conversations. Many, perhaps most, of my friends and acquaintances appear to be quite conservative, so the failure of the Voice proposal did not surprise me. Even a seemingly benign proposal for the inclusion of a First Nations Voice to Parliament in the Constitution was a bridge too far. As the Referendum campaigning continued, the widespread lack of knowledge was exploited by the Coalition’s powerful slogan, “If you don’t know, vote No”. And many did! The publicity garnered by the opposition of Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price was also extremely damaging to the ‘Yes’ cause. It’s also probable that the avalanche of conspiracy theorist podcasts and social media had some effect on the outcome. (I wrote brief analyses on two of these weird grab-bags of America-spawned misinformation for the SOFiA Newsletter.)

The Uluru Statement proposed ‘three key pillars of substantive reform’ – Voice, Treaty and Truth-telling. Right from the start, I thought that the sequence was back-to-front, as I feared that many Australians did not know, believe or care enough about the truth to vote in favour of A Voice to Parliament. Since the Referendum, some of the Uluru leaders have said as much themselves. So, the main point of my presentation today is that I believe that Australia should go back and, belatedly, “deal with the past”. What have been the effects of European colonisation on the First Australians and their descendants?

- Why we don’t know

Right from first contact, Europeans did not “get” Aboriginal people. They could not see that Aboriginals had any religion; they believed that they were simple, nomadic hunter-gatherers; that their languages lacked complexity and subtlety; and that they were unintelligent and lazy. Sixty millennia of separation had resulted in two branches of homo sapiens that looked, behaved and thought so utterly differently from each other that the other might have been aliens from outer space. Neither was sure that the other was even human, though the levels of incomprehension were not exactly the same – First Nations people soon learned that the white men were not the ghosts of ancestors, but many Europeans continued to think of Indigenous people as lesser species of humans well into the 20th Century.

After colonisation in 1788, the sheer size of the continent and related difficulties with transport and communication were continuing causes of coloniser ignorance. So, too, was the rapid pace of White seizure and occupation of First Nations’ land, district by district. In his research, Henry Reynolds has identified the limited extent to which information from the ever-receding frontier reached city-dwelling Australians.

My experience as an undergraduate student of Australian history in the 1950s and Reynolds’ as a university lecturer in the 1970s was that the history books at every level portrayed colonisation from the perspective of the victorious colonisers. The emphasis was on heroic pioneers overcoming horrific problems of climate, distance and isolation in a hitherto empty virgin land. In the rare mentions of indigenous people, they were, at best, an unimportant backdrop. By the end of the 19th Century, some might be useful as stockmen or domestics. But the few universities of the day were not the only “central” institutions that were relatively quiet about the events of regional colonisation. The colonial governments and city newspapers had an interest in some aspects of the process, but both were overwhelmingly controlled by and supportive of the big landholders. A few governors, politicians, clergymen and journalists did speak out against the brutal treatment of First Nations people, but this had very little effect. By the middle of the 20th Century, a great silence had descended on the subject.

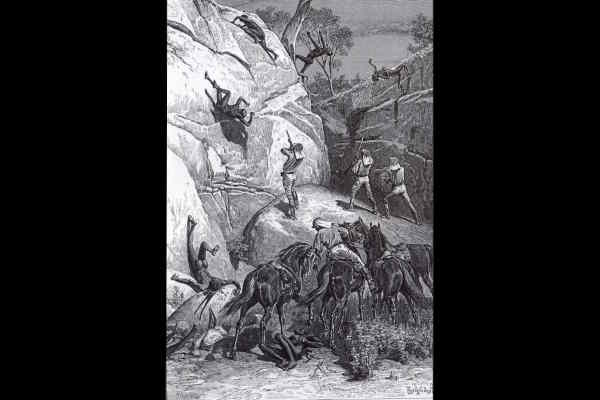

In a Eureka moment in Bowen, Reynolds realised that a wealth of detailed, accurate information about the history of colonisation did in fact exist, but that it had largely been restricted to the local areas. What he discovered was that detailed participant and eye-witness information was always there, but it had mostly not got past the local level. All round the country, it emerged, the local newspapers had reported, with artless frankness, the horrific treatment that had been meted out to the local Aboriginal people. Reports on the spearing of a stockman were often followed by much longer reports on settler retribution. Typically, a leading land-holder or magistrate would organise a posse to punish or “disperse” the local tribe. The names of the participants and eye-witnesses would be included – no attempt was made to hide their identity. Generally, the tone of reports suggests that the reprisals were accepted by the community as justifiable, however disproportionate the death-count might be.

In recent decades, a small army of researchers – historians, archaeologists, linguists and geneticists – have been working on First Nations issues, including the impact of colonisation. The primary and secondary sources they have been mining include: Local newspaper reports and editorials, police and court reports, council minutes, letters, diaries, memoirs and biographies. Increasingly, research teams have included Indigenous scholars. More comprehensive, balanced histories and biographies are now being written and a number of well-researched radio and television documentaries have been produced.

- What we need to know

What is it that all Australians need to know about the history of colonisation and its continuing deleterious effects? It’s true that information does not necessarily bring empathy, but it often helps. I shall begin with the words of one of the minority of colonists who were deeply shocked by the almost casual destruction of the lives and livelihoods of First Nations people, the poet, Henry Kendall. This is the first stanza of his poem, “The Last of his Tribe” of 1864:

He crouches, and buries his face on his knees,

And hides in the dark of his hair;

For he cannot look up to the storm-smitten trees,

Or think of the loneliness there—

Of the loss and the loneliness there.

So what were the details of “the loss” that we need to know? What were the cause and nature of “the loneliness”?

The overarching fact is that First Nations people were dispossessed of almost everything that matters. That is, they lost their ‘country’, to which they had deep cultural, spiritual and emotional attachment and dependence. As a result, they lost access to their food sources; they often lost family and friends; eventually, almost all lost their language. Sometimes, the dispossession led to death from hunger. It also led to mass death, sometimes from the side effects of the losses, but it often came more quickly, directly and violently.

The immediate cause of large numbers of deaths was infectious disease. At first contact, First Nations people had no immunity to European diseases, so smallpox, tuberculosis, measles and influenza killed many thousands. Later, loss of traditional food sources led to malnutrition and, when flour and sugar-based foods became available, to tooth decay and heart, kidney and liver disease. Later still, sexually transmitted and alcohol-based diseases became rife, as did generations of mental illness. The gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous health and longevity are still enormous. The gaps are not closing.

No issue is more contentious and more in need of clarification than the direct killing of Aboriginals by colonists. We shall never know the extent of shooting of one or two people at a time by early land-holders, but killings of a number of Aboriginals at a time were usually organised and recorded, at least in the local media listed above. I acknowledge that, until very recently, I would not have been able to name more than three or four such massacres. However, in recent decades, more and more have been dealt with in biographies and documentaries on radio and television and information has found its way into the history books studied at a tertiary level. The recent project of the University of Newcastle on Colonial Frontier Massacres should be a major source for further research and communication to a wider audience. I urge members to study the website for themselves. (By the way, a ‘massacre’ is defined as the attested killing of six or more people.) Briefly, the conservative estimates are that:

At least 10,732 ATSI people were killed by colonists in 403 massacres;

At least 160 colonists were killed by ATSI people in 13 massacres.

As far as I have seen, the Project reports have not attracted a great deal of adverse criticism. They have generally received favourable reviews from the ABC, SBS, “The Guardian” and the Channel 9 press. One of the contributors to “Quadrant” has charged the authors with plagiarism. So far there has apparently been no concerted attack by a group of conservative academics, as there was after the publication of “Dark Emu”.

My main point today is that the mass killing of First Nations people should be a priority focus of a renewed “truth-telling” campaign. While it may be the most confronting, it is based on objective facts, as the “stolen children” campaign was. It is fanciful to imagine that most Australians will study the findings of the Newcastle project, either in its present online form or in a subsequent written report. What is needed, then, is for the findings to be translated into more accessible forms such as: focused histories and biographies aimed at a more general readership; more media documentaries like “The Australian Wars”, the ABC television series of 2022; more biographies like David Marr’s “Killing for Country”; and more novels like Melissa Lukashenko’s “Edenglassie” (2023). The hardest tight-rope to walk will be for materials aimed at primary and secondary school children.

If telling the truth about colonisation is going to be hard-work, there is an even more difficult area that must be addressed – helping Australians understand the continuing disadvantage experienced by the descendants of First Nations people living today. It is much harder to find statistics and objective facts in this area. Many Australians do not believe that the sufferings of past generations are being “visited on the children to the third and fourth generations”. Jacinta Price says she doesn’t think they are. In the face of complaints from First Nations activists, the knee-jerk reaction is often – “Get over it!” and “I’m not responsible for the crimes of my great-grandparents!” Biographies, documentaries, novels, television series and articulate, popular First Nations leaders will need to play a part. It’s likely that further research in social sciences and medical sciences like sociology, psychology and neurology will clarify the nature of the life problems of today’s generations of Indigenous people and lead to better understanding and amelioration. That should help to paving the way for ‘closing the gap’.

That’s an issue I shall leave for someone else to take up at another time.

Here’s the link to the Newcastle project website:

https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/

Disclaimer: views represented in SOFiA articles are entirely the view of the respective authors and in no way represent an official SOFiA position. They are intended to stimulate thought, rather than present a final word on any topic.

(Image: Wikipedia)