Faithless fictional Fathers

Greg Spearritt reflects on some fiction from the Naughties.

(Original article published in the SOFiA Bulletin, March 2004)

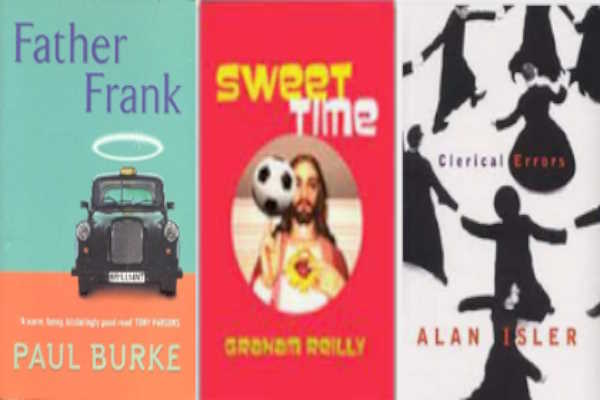

What do Catholic priests have over Baptist pastors or Anglican vicars that makes them so popular with writers of fiction? In a word: celibacy. In the celibate priest we find a unique potential for romance and for interesting variations on the theme of relationships. Combine this with the scandal/allure of the sceptical or non-believing priest, and you have the starting point for three witty novels.

Father Frank

The most ‘feel-good’ and least cynical of the three is Father Frank by Paul Burke (Hodder & Stoughton 2001).

Burke’s Frank Dempsey stumbles upon the priesthood and finds he both excels at and enjoys being a priest. This, in spite of being “not overly religious” and not believing just about everything he’s supposed to believe. Resigned to leaving the over-active sex life of his student days behind, Frank finds fulfillment in building up the community in his London parish. However, when Miss Right in the form of advertising executive Sarah Marshall appears, the inner (and eventually outer) turmoil begins. Loneliness, a theme common to all three novels, is a potent part of the mix:

A priest can be like a lonely child who makes up imaginary friends. Except that the priest falls back on God – the ultimate imaginary friend. (271)

On the matter of belief, Father Frank is – like the so-called ‘godless vicars’ of the UK SoF Network – essentially non-realist. Doctrine is entirely secondary, if not irrelevant, to the mission of the Church. Building community and helping people is what it’s all about. Unlike most of the SoF priests, though, Frank has to be Catholic. Non-believing Anglican clergy seem to have lost their shock value nowadays.

Sweet Time

Sweet Time by Graham Reilly (Hodder Headline 2004) is also in the ‘heart-warming’ category, but its take on the Church is much less benevolent.

Douglas Fairbanks is newly arrived from Scotland and on a mission to create a local soccer club in Baytown, Melbourne. His bride of just a few weeks, Kirstin, has rescued him from a lonely celibate life in a bleak Glasgow parish, but Douglas finds it hard to shake the influence of his former life and be the kind of husband his wife deserves:

The problem with your priests who wanted to quit the game at half-time was that they were terrified of being released into a world they had not been prepared for… Maybe it was better to be a shepherd than a bleating sheep in a large indifferent flock. (106)

The football club project turns out to be spiced with intrigue and humorously flavoured with a host of locals, ‘characters’ in the full sense of the word.

Though we come in Sweet Time to understand the potential of the Church in its own misogynist, authoritarian way to ‘stuff people up’, its role in providing sanctuary for the lonely and abused is also acknowledged – though perhaps not entirely as a positive thing, leading as it can to toying with the harder and more debilitating drug of lifetime commitment/priesthood.

The issue of religious belief in the novel is secondary to concerns about relationships:

A man and his dog, a man and his God. D-O-G. G-O-D. Was there that much of a difference? Douglas laughed to himself… Not one of the great metaphysical questions of all time, but one that may in the end reveal that the former relationship made more sense, although with the latter you did save on tins of Pal and vet’s fees. (27)

Clerical Errors

Broader in scope, witty rather than funny and much darker than either of the above is Alan Isler’s Clerical Errors (Jonathan Cape, 2001).

Isler’s character Edmond Music is a Jew, an atheist and a scholarly Catholic priest who for twenty-five years has shared a bed with his housekeeper.

In the once-vivacious and passionate Maude we see echoes of Mel Gibson, director of The Passion:

In her view, Catholicism was not to be fiddled with, not even by those sitting in the highest councils. Certainly, nothing was to be discarded. She knew what was true religion and what was not… It resided in the letter of the old law, not in the vaguenesses, the hesitations and the uncertainties of Vatican II. (207)

The illicit nature of her relationship with Edmond, his passive self-absorption and his clever but corrosive cynicism gradually sour their life together, and Edmond comes, finally and tragically, to learn that his love and affection are not just unreciprocated, but abhorred.

Though not quite likeable, Edmond Music is a much more interesting character than Father Frank or Douglas Fairbanks. He’s given to ruminating on life and meaning in ways that I found stimulating and provocative. For example:

I find myself… increasingly of the opinion that accident, chance and contingency rule individual lives, mine in particular. (11)

Having acknowledged that many of greater intellectual reach than he are devout believers, he muses:

Can it be that belief and doubt are genetically determined? Is there a switch that at conception or in the developing foetus may be turned on or off? I don’t profess to know. Proofs for religious truth are full of holes; proofs against are useless. Some seem predisposed to believe, and others not. I only know that what is plainly nonsense to me is an incontrovertible article of faith to another. (29)

And on the great themes of God and faith:

At the end of the second millennium, it is not easy to have faith in a benevolent, active God. In the west, in western Europe at least, we think those who profess to possess it deluded or lacking a few pence in the pound…

Most of us who care about such things, I dare say, have long since effected a divorce between faith and God. God has become something of an embarrassment, a paper tiger, a bug with which to frighten babes. What we have faith in today is universal evil, a harsh faith suited to grown-ups. We look about us and we see a world riddled with evil, a world in which we know all power is corrupt and all humanity debased. We know, moreover, that we can do nothing about any of it. (108-9)

Edmond’s cynicism goes too far even for me, though revelations about the doings of the big tech and fossil fuel companies (let alone the waging of war in Ukraine and Gaza) tempt me to wonder if he’s not, after all, a realist on this score. Nonetheless, his cynicism is entertaining: I tender his assessment of Tertullian’s exhortation to ‘believe because it is absurd’:

Suppose I had put it to the faithful as follows: ‘Know that the world and all that inhabits it – all of you, my dear little brothers and sisters, and even I myself – we are actually resident in the mind of a monstrous carp swimming languidly in the warm waters of Eternity. Certum est quia absurdum est.’ You see what I mean. It is not for nothing that the phrase ‘hocus-pocus’ derives from the words of consecration in the Mass, ‘Hoc est enim corpus meum’, and in turn gives birth to the word ‘hoax’. (8-9)

Of the three books, Clerical Errors is by far the meatiest. Whether you’re after a light snack or a three-course meal, you can select from the three to suit your appetite and fully expect not to be disappointed.

Disclaimer: views represented in SOFiA articles are entirely the view of the respective authors and in no way represent an official SOFiA position. They are intended to stimulate thought, rather than present a final word on any topic.