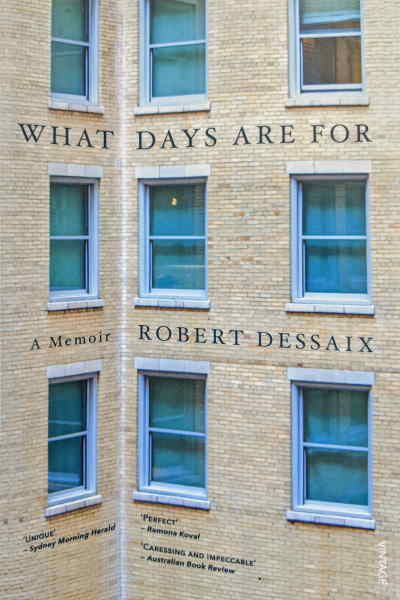

Dessaix, Robert – What Days Are For

Greg Spearritt reviews a stimulating contemplation on life and mortality.

Writers notoriously cannibalise the lives of family and friends, as well as their own, for the sake of a story. ‘Write what you know’ is a common piece of advice for new writers, though it’s not a philosophy without critics.

Robert Dessaix is clearly in favour of this approach. Night Letters (1996), for example, deals with the fictional character R who is coming to terms with the discovery that he is HIV-positive. The more recent What Days Are For (2014) is a semi-autobiographical reflection on life, spurred by a life-threatening heart turn which finds him bed-ridden in hospital, tethered to tubes and machines.

Days, says Dessaix, are where we live our lives. ‘Days’ is also the title of a short, but satisfying, Philip Larkin poem that Dessaix uses to great effect in exploring his topic.

How, he asks, can we spend our days in order to value them? Travel experiences loom large in Dessaix’s life, but so too do mundane, domestic events. Appreciating and reflecting on what you experience is an important part of the mix, whether it’s sampling Hindu rituals in Udaipur or just looking out the hospital window:

From up here on the tenth floor… Saturday night is a frozen cascade of lights to the west, etched with an icy brilliance into the black of the sky, soundless, beautiful past all imagining. (p.103)

Dessaix has an impishly curmudgeonous – if that’s not a word, it should be – streak, a penchant for shocking us into thinking for ourselves. This often manifests in wickedly humorous dogmatism, as for instance in his forthright claim at the 2021 Writer’s Festival in Brisbane that dogs have an inner life but cats don’t. (He may be right about dogs but I’m sure he’s wrong about cats.)

His take on religion is similarly provoking. Organised religion, he says,

cramps the imagination, but the masses don’t want imagination, they want familiar folk tales, maypole dancing and sorcery. (p.111)

Religion, he suspects, is “spirituality gone rotten”, though, bless his lack of a soul, he’s not fond of the term ‘spirituality’ either. Relevance, further, is anathema to religion:

How embarrassing it is when churchmen try to say something relevant after a massacre or earthquake. Leave relevance to the rescue services. What the victims want is comfortingly irrelevant codswallop. (p. 112)

Dessaix’s experience mirrors my own insofar as religion “usually metamorphoses into humanism”. (p. 114) He describes – entertainingly, as always – his own loss of religious faith, though he refers to himself as an ‘unbeliever’ rather than an atheist. Atheists in his view define ‘God’ and then declare such an entity doesn’t exist. Allow me to take a leaf out his own playbook and suggest this last claim is utter hogwash. Atheism, like religious belief, is not a choice. In important matters, we believe what rings true for us; it’s that simple. What rings true, of course, is a function of our life experiences, including the culture we’ve been raised in, what we read and who we meet.

What Days Are For is typical of Dessaix’s writing: wry and meandering, skillfully returning to the Theme and the setting before gambolling off in yet another direction. His love of language shines through. If you haven’t yet read this book, my advice is: gift yourself for Christmas. (Since I have, my gift will be his 2020 book The Time of Our Lives: growing older well.)

Robert Dessaix What Days Are For (Vintage, 2015)