The afterlife in Ancient Egypt

David Cohan presents some beliefs from Ancient Egypt concerning the Afterlife.

David is an atheist. He does not believe in Heaven, Hell, Afterlife, Resurrection or Reincarnation. He believes these doctrines do more harm than good. His favourite text from the Old Testament is:

Ecclesiastes 9:10 “Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might, for in the grave, where you are going, there is neither working nor planning nor knowledge nor wisdom.”

The Ancient Egyptian Afterlife

“The Egyptian afterlife was a mirror-image of life on earth. To the Egyptians, their country was the most blessed and perfect world.” [1]

Assuming the dead got through some trials (to be described), they would get to “The Field of Rushes”:

Life in the Field of Rushes was a reflection of the real world they had just left with blue skies, rivers and boats for travel, gods and goddesses to worship and fields and crops that needed to be ploughed and harvested. The dead were granted a plot of land in the Field of Rushes and were expected to maintain it, either by performing the labour themselves or getting their shabtis to work for them. Shabtis (small statuettes) were often supplied with agricultural tools such as baskets and hoes and were often led by a foreman or overseer (who appeared after about 1000 BCE), who carried a flail instead of tools. [2]

Rich and Poor

It would seem that, in their life after death, the rich stayed rich, and the poor stayed poor. This is very different from views such as can be found in Christian and Islamic traditions, which are typically egalitarian, or even offering benefit in afterlife as compensation for privation in this life. (Hopefully the Egyptian poor didn’t have to work quite as hard in the Afterlife as they presumably did in life.)

It would seem then, that the priests produced a belief system that told the rich what they wanted to hear. And also gave the priests plenty of work producing the texts the departed would need to achieve this afterlife of eternal bliss.

Ancient Egypt – The ‘Book of the Dead’

“Death was only a transition … Spells and images painted on tomb walls (known as The Coffin Texts, The Pyramid Texts, and The Egyptian Book of the Dead) and amulets attached to the body, were provided to remind the soul of its continued journey and to calm and direct it to leave the body and proceed on. [3]

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead is a collection of spells which enable the soul of the deceased to navigate the afterlife. The famous title was given the work by western scholars; the actual title would translate as The Book of Coming Forth by Day or Spells for Going Forth by Day.

A more apt translation to English would be ‘The Egyptian Book of Life’ as the purpose of the work is to assure one, not only of the survival of bodily death, but of the promise of eternal life in a realm very like the world the soul had left behind.” [4]

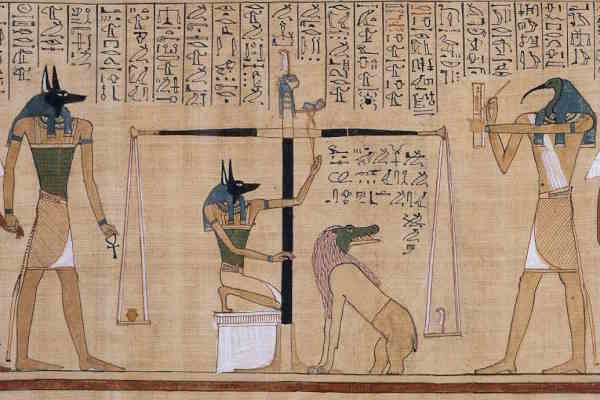

Weighing of the Heart Ceremony

“In Egyptian religion, the heart was the key to the afterlife. It was conceived as surviving death in the Netherworld, where it gave evidence for, or against, its possessor. It was thought that the heart was examined by Anubis and the deities during the weighing of the heart ceremony. If the heart weighed more than the feather of Maat, it was immediately consumed by the monster Ammit.” [5]

“There was no ‘hell’ in the Egyptian afterlife; non-existence was a far worse fate than any kind eternal damnation.” [6]

“Judgment of the Soul from the Papyrus of Hunefer. Shows Hunefer’s heart being weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth, by the jackal-headed Anubis. Ammit stands ready to eat the heart if it fails the test. The ibis-headed Thoth, scribe of the gods, records the result. ca. 1275 BCE, Nineteenth Dynasty. In the Book of the Dead, the deceased is given a series of declarations to recite at the Judgment of the Dead. The Declaration of Innocence was a list of 42 sins the deceased was innocent of committing. …

After the declarations are recited, their heart is weighted. If the heart was weighed less than the feather of Ma’at, the deceased was ruled to be pure.” [7]

Declaration of Innocence was a list of 42 sins, customised to suit the departed (e.g. Papyrus of Ani ~1250BCE; selection of 17 of these below)

- Hail, Usekh-nemmt, who comest forth from Anu, I have not committed sin.

- Hail, Hept-khet, who comest forth from Kher-aha, I have not committed robbery with violence.

- Hail, Fenti, who comest forth from Khemenu, I have not stolen.

- Hail, Am-khaibit, who comest forth from Qernet, I have not slain men and women.

- Hail, Neha-her, who comest forth from Rasta, I have not stolen grain.

- Hail, Neba, who comest and goest, I have not uttered lies.

- Hail, Qerrti, who comest forth from Amentet, I have not committed adultery.

- Hail, Ta-retiu, who comest forth from the night, I have not attacked any man.

- Hail, Unem-snef, who comest forth from the execution chamber, I am not a man of deceit.

- Hail, Unem-besek, who comest forth from Mabit, I have not stolen cultivated land.

- Hail, Neb-Maat, who comest forth from Maati, I have not been an eavesdropper.

- Hail, Tenemiu, who comest forth from Bast, I have not slandered anyone.

- Hail, Tutu, who comest forth from Ati, I have not debauched the wife of any man.

- Hail, Maa-antuf, who comest forth from Per-Menu, I have not polluted myself.

- Hail, Nekhenu, who comest forth from Heqat, I have not shut my ears to the words of truth.

- Hail, Kenemti, who comest forth from Kenmet, I have not blasphemed.

- Hail, Tem-Sepu, who comest forth from Tetu, I have not worked witchcraft against the king.

Ancient Egypt – Letters to the Dead, and Responses

“The justified dead, now in paradise, had the ear of the gods and could be persuaded to intercede on people’s behalf in answering questions, predicting the future, or defending the petitioner against injustice. …Letters to the Dead date from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 – 2181 BCE) through the Late Period of Ancient Egypt (525-332 BCE), essentially the entirety of Egyptian history.

When a tomb was constructed, depending upon one’s wealth and status, an offerings chapel was also built so that the soul could receive food and drink offerings on a daily basis. The letters to the dead, often written on an offering bowl, would be delivered to these chapels along with the food and drink and would then be read by the soul of the departed.

…A writer would receive a response from the dead in a number of different ways. One could hear from the deceased in a dream, receive some message or ‘sign’ in the course of a day, consult a seer, or simply find one’s problem suddenly resolved. The dead, after all, were in the company of the gods, and the gods were known to exist and, further, to mean only the best for human beings. There was no reason to doubt that one’s request had been heard and that one would receive an answer.” [8]

I believe the scribes/intellectuals of the adjacent Ancient Israel saw this interaction with the Dead as a distortion of life, and were against their own people having such beliefs.

Ancient Egypt – Alternate (Sceptical) Views of the Afterlife

“[Egyptian] view of the afterlife changed according to time and belief is reflected in some visions of the afterlife which deny its permanence and beauty. These interpretations do not belong to any one particular period but seem to crop up periodically throughout Egypt’s later history. They are particularly prominent, however, in the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) expressed in texts known as The Lay of the Harper (or Songs of the Harper) and Dispute Between a Man and His Ba (soul). The Lay of the Harper is so called because the inscriptions always include an image of a harpist. They are a collection of songs which reflect on death and the meaning of life. Dispute Between a Man and his Ba comes from the collection of texts known as Wisdom Literature which are often sceptical of the afterlife.

Some of the texts which comprise The Lay of the Harper affirm life after death clearly while others question it and some deny it completely. One example from c. 2000 BCE from the stele of Intef reads, in part, “hearts at rest/Hear not the cry of mourners at the tomb/Which have no meaning to the silent dead.” … In these versions, the afterlife is presented as either a myth people cling to or just as uncertain and tenuous as one’s life.” [9]

Article © David Cohan 2023

Disclaimer: views represented in SOFiA articles are entirely the view of the respective authors and in no way represent an official SOFiA position. They are intended to stimulate thought, rather than present a final word on any topic.

Photo: Wikipedia