Loving Linnaeus

An apologia by Greg Spearritt.

Speaking as one who has discovered the joy of amateur botany, it is obvious to me that there is no God. Any God worth its salt would have the names of plants stencilled on them for everyone to see, instead of requiring painstaking work with hand lens and plant key.

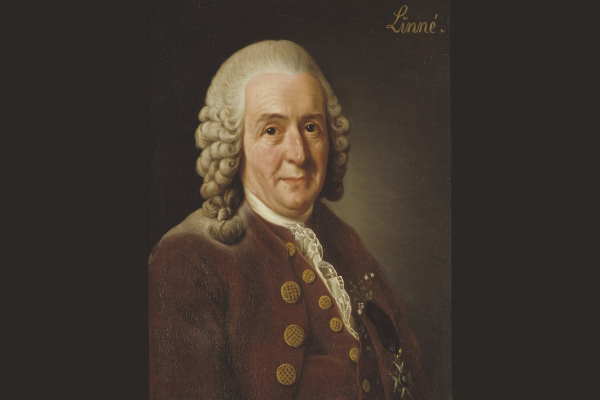

In the absence of such a God, Swede Carl Linnaeus (aka Carl von Linné) might perhaps be considered a demi-god.

Linnaeus came to be in 1707, and even as a child showed unusual interest in his natural surroundings. Though he also pioneered the study of ecology, he’s best known for his binomial system of classification for living things. His penchant for consistently naming things in this way – using genus and species – was an influential and revolutionary move.

Dr Carl was not, apparently, known for his humility. Nor, fortunately, was he known for an unhealthy obsession with sex, though as a qualified medical doctor he did specialise in the treatment of syphilis. One critic, Johann Siegesbeck, bemoaned the “loathsome harlotry” of Linnaeus in focusing on plant sex organs when classifying them – God would surely never have allowed the kind of licentious behaviour in plants that Linnaeus was describing. We’re told Carl got his revenge by naming an apparently useless weed Siegesbeckia.1. Pope Clement XIII was also offended, demanding in 1759 that all works by Linnaeus held by the Vatican be burned.

Given that he was born 102 years before Charles Darwin, Linnaeus is remarkable for assuming in his binomial system that humans are in fact animals. He rather blotted his copybook, of course, by giving the extant species of Homo the specific epithet sapiens, meaning ‘wise’. Even in a world without Twitter and TikTok it was pretty plain to see that was a mistake.2.

Carl was also, in keeping with his culture and times – and, it must be acknowledged, largely with ours – racist.

So yes, Linnaeus was a mixed bag, but his lasting legacy is a system of naming that enables us today to get a grip on the world’s amazing and fast-disappearing biodiversity.

His critics, however, were not restricted to the 18th century.

UK author John Fowles, chiefly a fiction writer, had a bone to pick with Linnaeus. For the record, Fowles (1926-2005) was a mixed bag also. Influenced by the existentialists, Fowles saw the absurdity of life and was an atheist, a fact he described as “a matter not of moral choice, but of human obligation”.3. He wrote some famous novels, including The Collector and The Magus. Post-mortem, his unpublished diaries revealed significant homophobia and anti-Semitism.

Fowles’s small 1979 book The Tree is reviewed in glowing terms almost universally. I, however, demur.

Fowles in this book takes what might be described as a Zen approach to nature. It must be experienced, and cannot be captured in words. Worse, it shouldn’t be ‘carved up’ through language, because that kills it. The western scientific project of naming things is an attempt to ‘own’ them, to pin them to a board like hapless, lifeless butterflies. It has little to do with appreciating nature, and all to do with western acquisitiveness and the drive to exploit. The urge to know everything intellectually, says Fowles, if fulfilled, would be catastrophic for our species: it would “extinguish its soul, lose it all pleasure and reason for living”.4.

Fowles finds it “poetically just” that Linnaeus “should have gone mad at the end of his life”.5. This seems to be something of an uncharitable misreading of his actual end: his health certainly declined, but it was a series of strokes which robbed him of the ability to recognise himself as the author of his own writings, though he could still admire them.

I don’t suggest that The Tree has no valid point to make. Its thesis concerning science is a necessary, if unoriginal, criticism. We certainly can go overboard about classifying and analysing, and there is definitely an acquisitive aspect to that project, as though the natural world were pokemons and we the pre-teens with the compulsion to “collect ‘em all”. This places us at a remove from our world, and I can see how there is danger there of impoverishment.

A more concise (and to my eye, more eloquent) presentation of this idea can be found in a 1976 passage from Erich Fromm, referencing DT Suzuki’s comparison of two poems: ‘Flower in a Crannied Wall’ by Alfred Tennyson and a haiku by 17th-century Japanese Zen poet Basho. Tennyson sees a flower and plucks it out, “root and all”, seeking knowledge; Basho simply admires it in situ.

Rational thought is not overly prized in Zen Buddhism. One Zen master explicitly says:

The more you talk and think about it, the further astray you wander from the truth. Stop talking and thinking and there is nothing you will not be able to know. 6.

We could, presumably, choose not to think but just to ‘experience’. As I have noted elsewhere, however, any kind of reflection on that experience must involve language. And if we don’t ever reflect on what we experience, communicating it to ourselves (let alone anyone else), have we actually had the experience? What does it avail us, I wonder, to know everything but be unable to articulate any of it? If I experience absolute bliss but am unable to tell anyone or even think about it, how can my experience be distinguished from fantasy? 7.

Humans are language users, and language inevitably chops up the world. In its broadest sense, language is the water in which we swim. As English philosopher of religion Don Cupitt says, if you want to claim something is beyond language, please tell us about it in something other than language. The moment you speak, or send out a sign, or think, you are immersed in the entirely-human and culturally- and historically-locatable world of language.

While I acknowledge the risks, the scientific endeavour to describe and analyse brings me great delight. For me, talking and thinking are irreplaceable ways of integrating and savouring experience – of savouring life.

Forest bathing is apparently a thing, and by all accounts it can be very beneficial. But it need not discount the value, on a different sort of walk, of knowing one plant from another. That kind of walk becomes rather like greeting old friends.

My world was greatly enriched when I began, some decades ago, looking for plants to make a garden that would attract birds. You might recall those ‘magic eye’ puzzles where a cleverly-designed two-dimensional pattern on a page, when viewed the right way, suddenly reveals a three-D object or scene. In the same way, my nascent awareness of native plants made a whole new dimension of the world suddenly appear. I began to see plants that I passed every day but had never ‘seen’. They simply hadn’t existed for me before that.

If all you ever want to see is a forest – a wall of green – that’s up to you. I do want to see a forest, but I also want to see, and appreciate, the trees (and shrubs and herbs…). Knowing one from another, and being able to call them by name, enables me to understand and appreciate their unique properties. To be sure, these are ‘artificial’ monikers, always inadequate. But they actually help me ‘connect with nature’ and see the world as all the more miraculous.

So to Linnaeus I say: well done, you. You’re not the be all and end all, but no-one ever said you had to be.

- See https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/linnaeus.html. Sigesbeckia orientalis – Common St Paul’s Wort – is in fact native to Queensland, as well as to parts of Europe.

- To be fair, he initially named us Homo diurnis, ‘man of the day’. To go with the soup, perhaps?

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Fowles#cite_ref-13

- The Tree (Vintage, 1979) p.49

- Ibid, p.29

- From Verses on the Faith Mindby Chien-chih Seng-ts’an, Third Zen Patriarch (606CE).

- Don Cupitt makes just this point in What is a Story (SCM 1991) p. 177.

Disclaimer: views represented in SOFiA articles are entirely the view of the respective authors and in no way represent an official SOFiA position. They are intended to stimulate thought, rather than present a final word on any topic.

Image: Wikimedia Commons