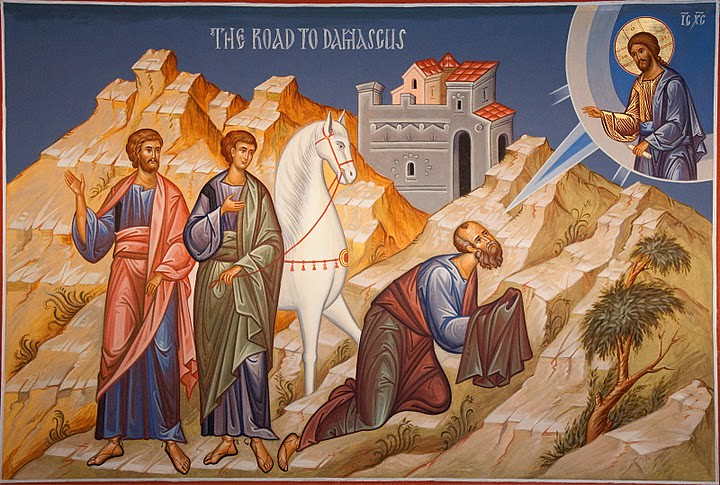

John Carr reviews Damascus by Christos Tsiolkas (Allen & Unwin, 2019)

Australian author, Christos Tsiolkas, has had great success with his earlier novels, particularly The Slap and Barracuda, both of which were made into television mini-series for the ABC. His most recent book, Damascus, is significantly different in a number of respects, but especially in that it has a historical setting and characters. Based loosely on the life of St Paul, it should be a breeze to market, as a couple of billion people already know something about Paul’s life and enigmatic character from his Epistles and the Book of Acts. However, it is not an easy or comfortable book to read. It explores serious issues – historical, religious and psychological – and paints a picture of people whose lives were blighted by almost unrelieved brutality, suffering and injustice.

In the first page of the book, set in 35 AD, the reader is plunged into a horrific, barbaric event, the stoning of a young Jewish girl condemned to death for fornication. It is told from the perspective of the terrified girl herself, bound and hooded. Her seducer and accuser is one of the men carrying out the stoning and her Pharisaic prosecutor, observing from the sidelines, is Saul. The following six chapters, set across the Roman Empire, all include Saul/Paul as a character, except for one, which is set in Ephesus more than 20 years after his death. Some of the characters are Biblical, including Thomas, James, Timothy and Lydia, while others are largely or entirely fictitious. One of Paul’s imagined Roman jailers, Vrasas, plays a major role, as does Able, a renamed and fictionalised version of Onesimus, Philemon’s runaway slave.

In all episodes, the brutality of First Century life is depicted in detail. Poverty. misogyny, slavery and violence all appear to be expected and, largely, accepted as normal – Greeks, Jews, Romans, it makes no difference. Except, that is, for the members of the shadowy underground Jesus Movement, who have been taught to love peace and their fellow Christians, whatever their past. Compared with pagans, they are blind to race, class and gender. But like devout Greeks, Jews and Romans, the Christians are manically fervent in their Faith and, even more than the pagans, are quite prepared to suffer torture and martyrdom for it. Even more than devout pagans, they are committed to quite specific beliefs and practices and have no patience with other views, however slight the difference appears to the outsider. The divisive questions that led to 2,000 years of division and schism within Christianity are already present – who exactly was Jesus, what was his relationship to the Hebrew God and what was his true message?

For readers with an interest in theology, Tsiolkas’s apparent views on these questions may be enough to sustain them through the drama and pain of the events. Paul’s disputes with the Jerusalem apostles that we hear about in the Epistles and Acts are explored in some detail. For the modern Christian, the battle over the right of Gentiles to become Christian without becoming Jews is no longer an issue, but some of the other divisive issues explored here remain with us to this day. Mainstream Christians will almost certainly call foul at the doctrines put into the mouths of Thomas, Timothy and Paul himself. For those of us with a less than passionate interest in the precise definitions of the Persons of the Trinity as battled over for centuries and set down in legalistic precision in the Nicene and Athanasian creeds, there are other issues to think about.

In the wake of Tsiolkas’s earlier books, it was expected that his Paul would be gay, seriously conflicted by the Hebrew Law. This is certainly how he is depicted — in both thought and action he is shown to be sexually and emotionally attracted to men. However, homosexual acts are much more common in Damascus than just those involving Paul. Few of these encounters are tender or life-affirming, but more typical of the types of violent homosexual attacks perpetrated by possibly gay men adopting homophobic attitudes and behaviour to cover up their own sexuality. It must also be said that there are more homoerotic descriptions than would be usual from a straight writer and an obsession with circumcision. But many Church-goers, startled a few times a year by liturgical readings of the Letter to the Romans, probably think that Paul can be accused of that, too. As expected, this fictionalised Paul also agonizes over the legitimacy of his claim to be an Apostle.

One of Tsiolkas’s themes that struck a chord with me was his exploration of the effects of the central doctrine of the Second Coming. To his credit, Tsiolkas’s Paul recognizes the cruelty of the continuing promise of imminent salvation to the suffering members of the ‘third and fourth generations’ of believers: They remain passionately committed to their prayer, ‘Come, Jesus, come!’ even as their fellow Christians die around them. God knows, they needed Jesus’s promise to be true and can be forgiven if they thought they were being conned.

So where are the personal beliefs of Christos Tsiolkas, a non-theist brought up within the Greek Orthodox Faith? Throughout, he presents the ethics of Christianity as a good starting point for living – ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ Like many liberal and progressive Christians, he views Jesus merely as a ‘good man’, a great teacher. Thomas is his main mouthpiece for this view, Thomas, who had the task of burying his ‘twin’ and believes that it is only Jesus’ words that survived. Like many others, Tsiolkas believes that the facts of human sexual reproduction have been seriously warped by the Abrahamic religions. His liberal contemporary views on the naturalness of sex are most clearly articulated by a pagan, the Priestess of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus. ‘Your brethren’, she tells Timothy, ‘hate that our bodies give birth to children’ (p 299).

In preparing to write Damascus, Tsiolkas undertook a great deal of research, reading the Bible, the Qur’an, the gnostic gospels and many biographies of Paul. But this is a novel, not a history book, and Tsiolkas’s Paul is drawn from his imagination as much as from the fragments of his life that history can provide for us. Nevertheless, depending on our own knowledge and beliefs, we may be able to develop a richer understanding of what he might have been like, both as a man and as the most influential Christian of all. Personally, I value even more the insights I gained of what it might have been like to be an inhabitant of the Roman Empire in the First Century. There is nothing abstract about Tsiolkas’s depiction of life; it abounds in flesh and blood, pain and terror, and some moments of hope and joy.

Photo by Ted on Flickr (Creative Commons License)