Marie Cameron reviews Cynthia Bourgeault’s The Meaning of Mary Magdalene (Penguin, 2013).

Recent years have seen a huge growth of interest in Mary Magdalene, whose reputation has been so suppressed and distorted by the Church but who was undeniably a close follower of Jesus and an important figure in the early Christian movement.

This interest reached its peak with the release of the 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code, which provoked an angry response from various Church figures.

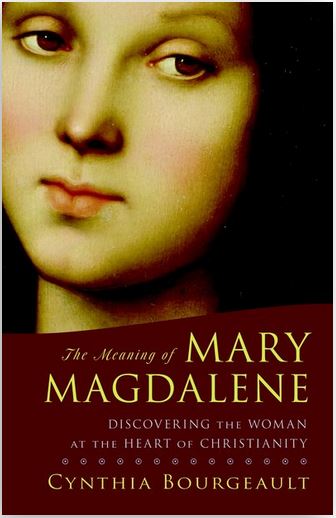

In her book The Meaning of Mary Magdalene, the scholar, contemplative and Episcopal priest Cynthia Bourgeault takes a careful analytical look at what we can know about this mysterious woman and her relationship with Jesus.

She begins by listing and examining all references to Magdalene in the four canonical gospels, which in fact provide quite a deal of information, before looking at her subject as she is presented in the non-canonical gospels of Thomas, Philip and Mary Magdalene. Bourgeault then outlines how the Church has misrepresented Magdalene in succeeding centuries, most significantly Pope Gregory the Great in the 6th century who identified her without a shred of Scriptural evidence as a prostitute. This is how we have been taught to see her ever since.

Bourgeault points out that Luke describes the male disciples, the Eleven, as having “companions” and that Magdalene is described in the Gospel of Philip as Jesus’ “companion”. The Greek word koinonos usually means “partner or spouse” and thus it is entirely possible that the inner circle of male disciples had their wives with them, and that Magdalene was the intimate and beloved partner of Jesus.

Further, the non-canonical gospels depict a clash over leadership between Mary Magdalene and Peter, who is clearly jealous of the special relationship between Mary and Jesus leading to her privileged position within the community, and questions why a woman should hold such a position.

The major part of the book is devoted to exploring the quest for spiritual union and enlightenment on which Jesus and Mary embarked, and the ways in which this quest relied on the transfiguration of eros into profound agapeic love, based on the three pillars of kenosis (self-emptying), abundance and singleness (the attained state of non-duality), which are spelled out more clearly in the non-canonical gospels than in the canonical gospels.

The author makes a persuasive case for the existence of this deep relationship between Jesus and Mary, which may well have included a sexual relationship, and demonstrates that the Church’s valuing of celibacy as the purest and holiest form of existence cannot be found in the teaching and practice of Jesus.

It is harder to follow Bourgeault into some of her more speculative theories, such as Mary Magdalene as a practitioner of anointing who introduced this practice to Jesus. For me, the jury is still out on some of these ideas.

The value of this book is in bringing Mary Magdalene vividly to life as a loving, passionate woman of deep spiritual understanding who was a close companion of Jesus, and in demonstrating why serious students of Jesus and the early Christian movement should study non-canonical as well as canonical writings.

Perhaps we should also question why these lesser known Gospels are not part of the canon, and whether they should be, as they clearly expand our knowledge of the breadth and depth of the teaching of Jesus.

But this may be a bridge too far for the average pew-sitter, who is likely to be scandalised by Bourgeault’s arguments.

Disclaimer: views represented in SOFiA articles are entirely the view of the respective authors and in no way represent an official SOFiA position.